This week has been the reality check for me: They aren't. Even the "high achievers" either aren't doing the reading or they are doing it and not understanding it. Even the AP students in some cases. These are kids who get A's in everything, who can write and articulate intelligent arguments. And they aren't reading what we assign.

These are the kids who are getting accepted left and right to Purdue and Brown and Cornell and UCLA and Cal. These are the best kids from the best school in the best area.

The real tragedy is that these are the exact kids who need the beauty and the breath of fresh air that comes with a good book. The bookroom is filled with titles that I would have killed to teach at previous schools - Kite Runner, Me Talk Pretty One Day, Sula, The Things They Carried, Things Fall Apart, The Namesake, Their Eyes Were Watching God, Indian Country, Slaughterhouse Five, Pride and Prejudice, Man's Search For Meaning...our bookroom has hundreds of choices.

Hundreds of choices that our students pretend to read or understand for most of their four years here.

I'm not pointing fingers at my colleagues - I assigned reading homework last semester, and many of my students told me they didn't read all of those books either. And some of them got A's from me too. So we're taking kids who love reading, who read for pleasure, who will do homework, who are compliant, and churning out students addicted to Sparknotes, trained to jump into the point in the discussion where their failure to read or understand will be noticed least, and who think that literature is just an excuse for a treasure hunt for symbols that they can identify and spit back out on a test.

So what's going on? And more importantly, how do we fix it?

If we believe that teaching through literature is the Right Way, and that the skills developed through beautiful literature can help students see their own life more clearly, analyse more carefully, and engage with the world more actively, then it's imperative we figure this out. And I'm the least capable person to figure this out, because I did all the assigned reading in high school and college, loved it, and understood the vast majority of it.

So I asked my students. In a previous post, I outlined the process we went through to ascertain what would be the best reading strategy for them. I would encourage you to read that before continuing with this post.

So here's are some of the take-aways from that mini-unit.

First of all, it's different for every group of students. That makes sense - any teacher can tell you that the climate of one section can be wildly different to another section of the same class. But how often have we treated them the same in the method we use for reading? I know I have.

Secondly, it will be a system of trial and error. When we came up with the plan, I had a student ask, "What happens if we end up not liking this, or it doesn't work - are we stuck with it?" NO! The whole purpose in giving them voice and choice is to make it work for them. Why would I force them to stick with something that wasn't working just because "they chose it"?

Thirdly, students are not used to being asked these questions. They haven't thought about it either, on the whole. They never think to question their teachers. They said to me, when I asked why they don't question what we're doing, "But we just assume that either you have a reason or that it would be rude to ask. So we don't ask why." I died a little inside on that one. Any student, regardless of age or ethnicity or grade level or ability, should be able to respectfully ask the teacher for rationale behind any assignment. And if the teacher doesn't have one, it should prompt some serious reflection on the teacher's part. I told my students that I would never ask them to do something for which I couldn't articulate a reason.

Finally, it's not enough just to have class discussions or to have students reflect on what they're learning and why. Students need to be given far more voice and choice than they usually get in factory-style education. I've found, over and over, that when I ask them for input, their ideas and cognitive process are amazing...often better than what Andrew and I came up with. Most of the plans are a result of students advocating for what they need, and trying to take ownership over their education. I'm confident that more students will be reading the assigned novels for these courses. And it's not because they like me. It's because they feel like it was their choice, and that if they have something to say about the process, the product, or the text itself, they have the freedom to say it. They don't have to hide the fact that they hate the book - in fact, sometimes that's the start of the best discussions in my classroom. And if they honestly aren't reading at home, how is it helpful to act out a farce in which we all pretend they ARE reading? It's teaching them that education has shortcuts. That they can get all of the answers off the internet.*

Is that really what we want to be teaching them?

*side note: When I said that many of my PLN agree that "if you can google it, it's not a good question to include on a test" they just couldn't understand what a test would look like with information that wasn't googleable. I gave some examples, such as: instead of memorising the dates of the Civil War (googleable), argue whether or not Lincoln did enough to prevent the war (not googleable). Their words: "Yeah, that second option is way more interesting and useful." Yes. Yes, it is.

Below the fold are the specific plans that we worked out in each of my three classes that have started a novel.

American Literature:

1st period

Problem: These students struggle to comprehend what they read the first time through, and struggle to complete reading at home. Most report leaving it until last, and by the time they've finished hour three or four of homework, they can't concentrate properly, or they run out of time, or they fall asleep.

Solution: They asked if they could do a big picture overview BEFORE reading the text in depth. So we will be reading it or watching a comparable movie (say, for plays or very faithful adaptations) before we get into textual analysis. The overview, and the close reading that follows, will be done in class, out loud, together. So after we do the big picture overview, we will focus in on scenes or sections where we can really dig into the text. We are looking for things like theme, character, plot, literary devices, motivations...the same stuff they usually are asked to find.

Rationale: The major difference is that students will get to know the text and characters before having to deconstruct them completely. It does make sense; imagine, for instance, going in to a psychologist to get some help on a few problems you're having. Instead of listening to your whole story, asking clarifying questions, trying to understand, imagine that the psychologist starts making judgements about you from the first few sentences you give. You wouldn't feel heard, understood, or helped. Yet we ask students to make judgements about characters from page 1. With the Big Picture Overview coming before judgements, we're asking them to examine all the evidence before they diagnose what a character wants or needs, and what makes them unique. Then, once they know the arc of a character, they can go back to specific pieces of evidence to examine them more fully. It's much closer to how we read in college in most English classes. You read the book before the first lecture on it, then you have discussions that are focused on a theme, issue, character, whatever, but you cover the whole book for each topic.

4th period

Problem: Half the class loves reading at home and hates reading in class, and the other half loves reading in class and hates reading at home. Most of the "I hate reading at home" students hate it because they struggle to comprehend it. They didn't mind having homework, so long as it isn't "read 25 pages by tomorrow" - the length of the assignment and the amount of time given needed to be reasonable and less than what they had been given in the past. They wanted choice in when things were due.

Solution: I assign them reading as homework twice a week. Each time, I try to keep it under 15 pages. If there is a relevant movie/play version, I post that section in their playlist as well. They have the choice to read or watch the movie/play version as homework. Then they come to class and we analyse that same section in class. So their homework is essentially a first read, and in class is the second.

Rationale: The kids who choose the movie/play version are the same kids who used to use Sparknotes in place of reading. I'd much rather them watch the movie than use Sparknotes as their primary source of information. It also gives them a choice - and so far, it's pretty evenly split between students reading and students watching. Then, we read about 85% of the text together in class, and they don't have to work to understand the basics of what's going on. Instead, we can focus on the fun, important, and analytical stuff. The level of their discussion has been so much higher than what I saw at any point last semester.

Humanities:

2nd period

Problem: They are addicted to Sparknotes because they want good grades, but either can't comprehend the assigned text, don't have time to read it properly, or just don't like reading. About half like to be read to, and the other half hates being read to. They also seem to be scared to have whole-class discussions, and would much rather write an essay than talk as a whole group.

Solution: We have two that we're going to try actually:

- In class, we play the ShowMe videos of me reading (such as these for Night) the novel. During the video, we all use Today's Meet as a backchannel discussion. That way, I can monitor comprehension, and students can throw out ideas that interest them most, or just comment on the plot in real-time.

- Have "Silent Reading" time in class when reading is required, with three options: 1) read the assigned section silently, 2) use their devices and headphones (or use a class device, as I have several to loan out) to listen to the video of me reading to them, or 3) read at home and use the class time for reading something else.

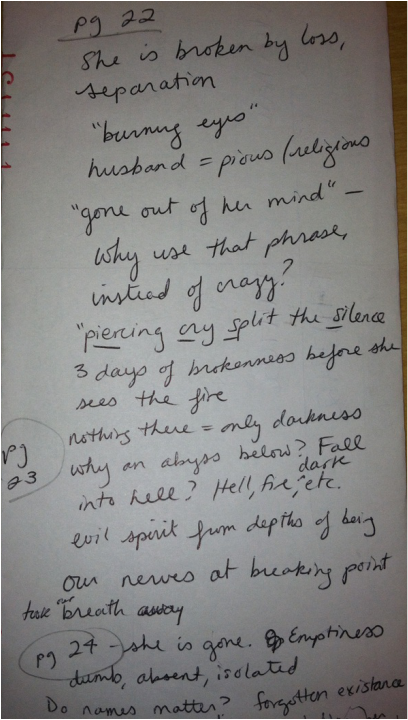

Rationale: Both options allow for students to complete all work during class time, but also keeps the reading to a faster pace than the pace set by traditional "reading the book out loud." The video for chapter 2 of Night is about 7 minutes long. So I gave them 10 minutes to of "Silent Reading" time. All students were able to finish it in that time. With other interruptions or questions, or just my own scatteredness, it has taken almost double that amount of time to read aloud to students live. There is also one more really cool thing we're doing. We are trying Reading Journals. Immediately after reading time, students have a few minutes to check their understanding, ask questions, etc. Then I have them write their thoughts, observations, questions, comments, frustrations, or just favourite/interesting quotes afterwards. Finally, students share with their table groups and then with the whole class. Some of the most interesting, amazing, beautiful and analytical examples have been given already - stuff I would have pointed out myself. But I didn't need to, because they saw it on their own. So they got to own that success. They also could use someone else's idea if they didn't feel confident sharing their own.

Here's a picture of my Real Live Reading Journal from Chapter 2 of Night:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed