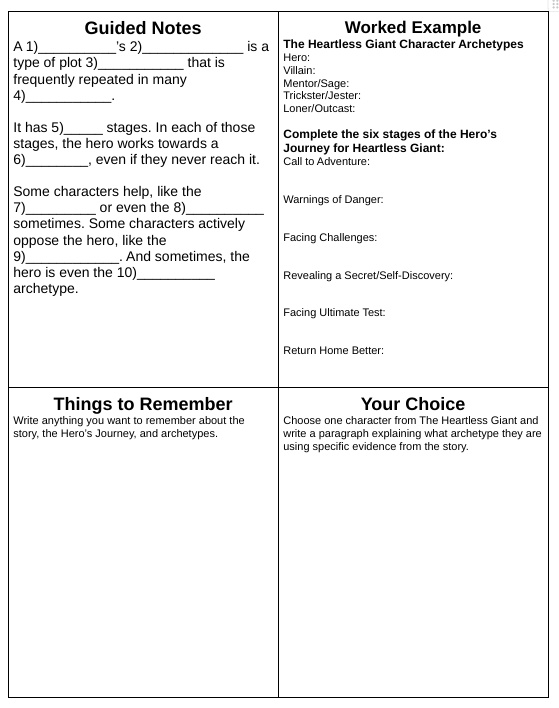

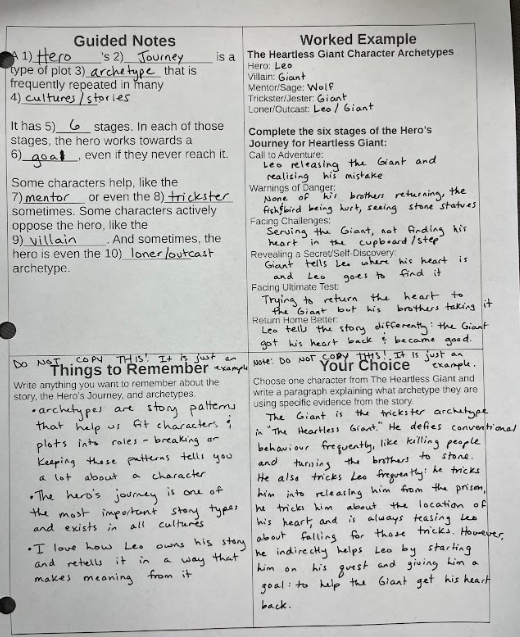

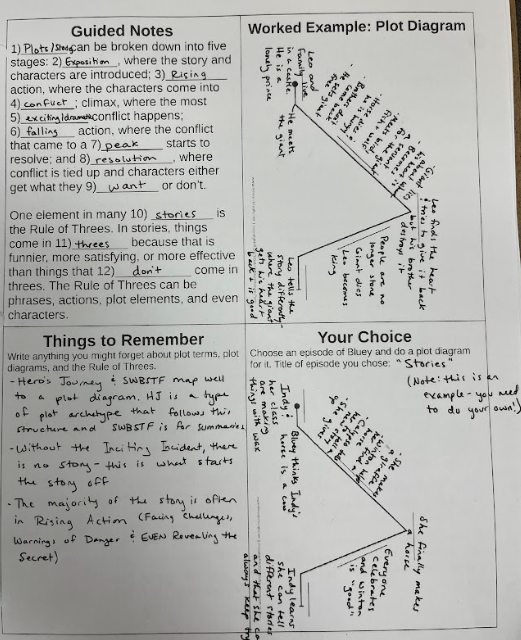

As we begin to approach the narrative writing at the end of the unit, we are building all the skills to understand plot, pacing, and voice. For about a dozen stories, students have charted the plot, done SWBSTF summaries and hero's journey maps, and looked at action/reactions and who is driving the action of the story. We've done that through looking at character archetypes and talking about what role those archetypes generally play in stories, and how they influence different parts of the plot.

All of those things involve looking at story patterns - how are stories and characters likely to behave. That will build the basis for the system of patterning I teach students to make meaning out of texts. It will also help them as they use the same resources and patterns to write their own story.

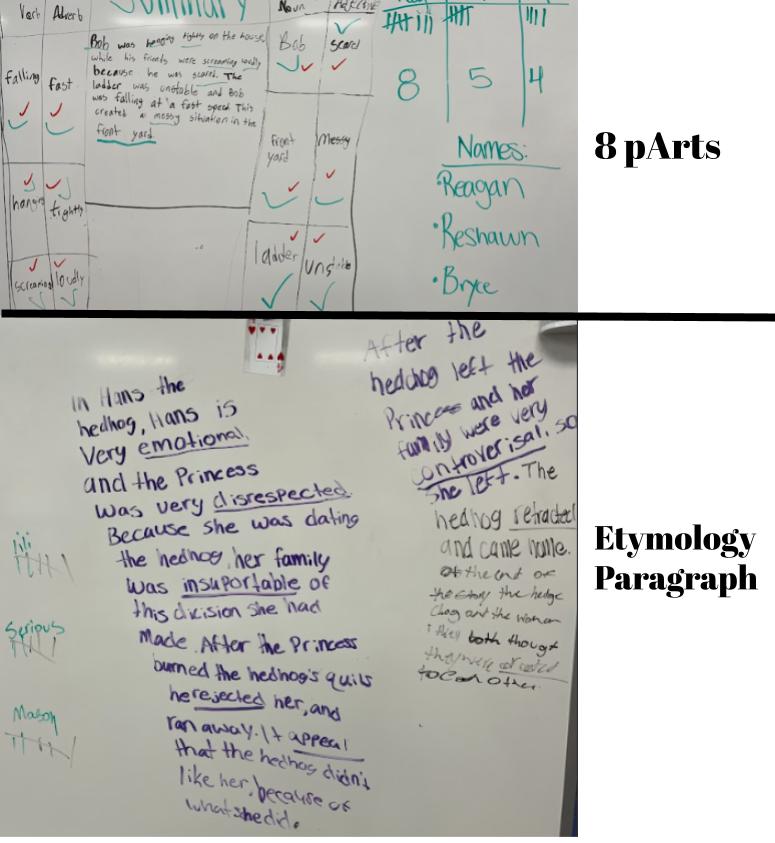

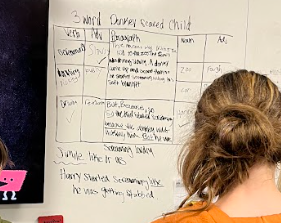

For many, it will be the first "essay" they've ever written. To prepare, they've written probably 20-25 paragraphs already, including six narrative paragraphs; hopefully one of those will yield a story they can turn into a longer piece. My hope was that by doing one a week, it would feel less overwhelming when I asked them to brainstorm possible stories.

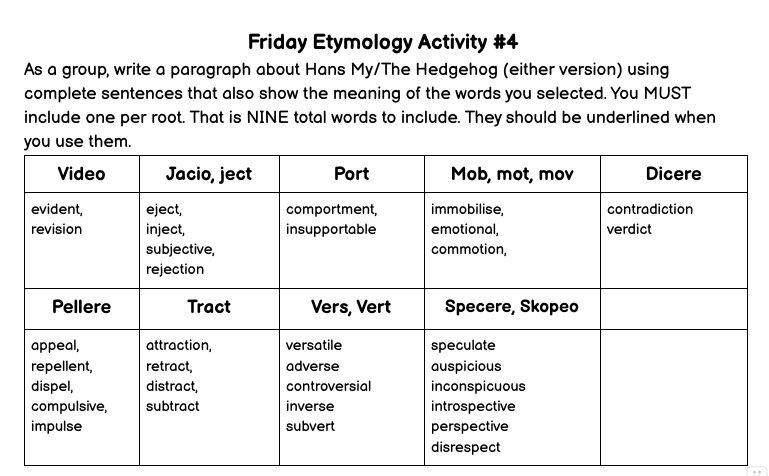

To help students build on their ability to choose the right words and establish a writer's voice, I went looking for short lessons that I could easily incorporate in the BTC model.

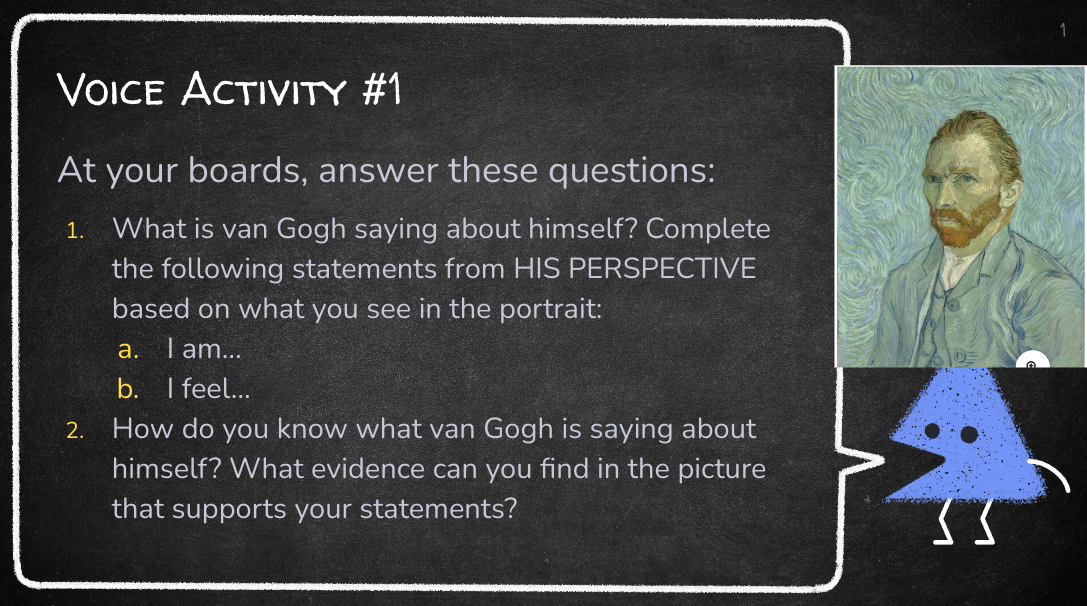

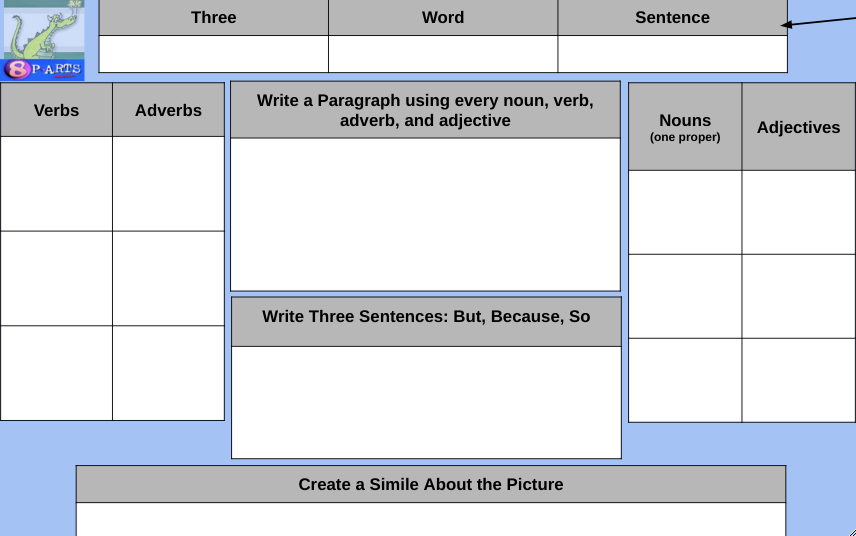

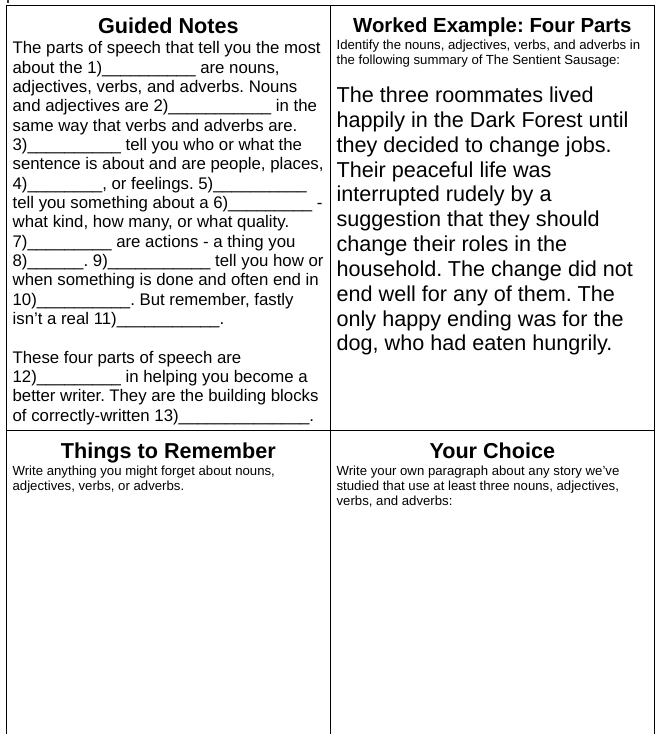

I stumbled on a Kindle Unlimited book called Discovering Voice: Lessons to Teach Reading and Writing of Complex Text by Nancy Dean. What I like about it is that the lessons are short, and they're complex enough for high school students, but simple enough for middle school. I've compiled them into slides to use in class. Here's the first activity:

The book builds from visual art to music to short texts, then longer ones. I haven't used the longer texts yet, but I love how it builds the idea of "perfect words" and encourages students to think about what writers do as making choices. Everything is a choice - just like with life.

Good writing should teach us about life, and that major theme of thinking carefully about our own choices and the choices of others is one that students desperately need. The Stoic dichotomy of control is something that I come back to a lot, both with my own choices and in counseling students about the choices they make.

That's all I've got this week. Hopefully I'll have something more connected to say next week.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed